Sustainability And Historic Preservation: Options And Opportunities In DC

Older building materials and practices allow some historic buildings to achieve unexpected energy efficiency. Often more significant, however, is the embodied energy derived from an existing building’s construction and maintenance.

The Building Innovation Hub recently published the following piece, by DC Historic Preservation Review Board Member Andrew Aurbach and BBB's Gretchen Pfaehler, about the aligned goals of sustainability and preservation in Washington DC and beyond.

Introduction

Recent dialogue across the District of Columbia and nationwide has put a spotlight on the relationship and compatibility between preserving the character of existing, historic building stock and improving building performance. Indeed, the National Trust for Historic Preservation has, since 2009, made this a cornerstone of its efforts.

“At a time of increasing concern about climate change, over-consumption of energy, and rapid depletion of natural resources, [preservation] reminds us that buildings are renewable, not disposable. Preserving, retrofitting and reusing them is a commonsense way to best use these assets while reducing the harmful environmental impacts caused by demolition and new construction. It’s a simple matter of wise stewardship – and that’s what sustainability is all about.”

—Richard Moe, President, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Preservation Magazine, July/Aug 2009Historic preservation is inherently compatible with sustainability strategies because preservation is fundamentally about utilizing what we already have, and sustainability is about stewarding existing resources to avoid harm to future generations. The best approach is to maximize the potential of existing buildings in a way that is aligned with the often quoted statement on sustainable development from the Brundtland Commission report, “Our Common Future”:

“Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

—Brundtland Commission report, Our Common Future, 1987Adaptability for Longevity

Older structures are generally more energy efficient because they utilized sustainable construction practices and planned obsolescence didn’t yet exist so buildings and materials were made to last and be repaired to continue their service. They were generally built in an era that pre-dates modern climate control systems (e.g. active mechanical and ventilation systems) and as such employed more durable building materials such as brick, stucco, and stone. Such natural materials also obviate the need for toxins and glues to hold the structure together, thus creating a healthier interior environment. These natural materials were commonly from relatively local sources, thus reducing the vehicle miles traveled and energy in transport.

In addition to the natural materials featured in older structures, the design practices utilized a variety of time-tested techniques which are re-emerging in new building design. This includes carefully oriented openings for doors and windows; natural ventilation in the eaves and other openings, allowing for hot air to escape in the summer months; porches and overhangs, which provide shading; and an orientation/sighting to maximize prevailing winds and airflow during temperate weather.

As has been demonstrated, older structures are more conducive to adaptive re-use. In countless cities around the United States, factories and warehouses have been adapted into “funky” housing and neighborhoods, such as the Pearl District in Portland, or the Light House and Cady’s Alley in Georgetown, DC. The bones of these structures enable flexibility of interior space such that any use could take place, from the original manufacturing and storage of the 1800’s, to commercial use in the 1900’s and residential space in the 2000’s. The adaptive re-use of these structures maintains a sense of place and culture for the respective neighborhoods, even if the use changes over time. As Jason McLennan notes in The Philosophy of Sustainable Design, “something that has been carefully designed and built is more likely to be re-used when its original functional life is over, even if it does not have historical value.”

Embodied Energy is the Equalizer

When discussion centers on building efficiency, the conversation is based on operating energy—how much energy is used to heat, cool, and maintain the structure. However, there is often a disconnect because the analysis often excludes the energy currently contained, or embodied, in an existing structure. The embodied energy (also referred to as embodied carbon) in a building has already been expended in the construction. This includes the energy required to manufacture the basic materials, to transport the materials, prepare the building site, as well as any maintenance that has taken place through the life-cycle of the structure. If a building is demolished, then the embodied energy contained within is completely lost. With the exception of some minor recycling, the demolition of historic structures wastes reusable assets, with the resulting materials expended into landfills. Preservation minimizes both the embodied energy and saves on new energy resulting in a significantly smaller energy footprint, thus a small carbon footprint.

“Seeking salvation through green building fails to account for the overwhelming vastness of the existing building stock…We cannot build our way to sustainability; we must conserve our way to it.”

—Architect Carl Elefante, author of “The Greenest Building Is…One That Is Already Built”Embodied energy calculators demonstrate that the consumption required for a new construction can be 15-30 times the annual energy consumption of the building over the life of the building. As a result, true sustainability is when a building is made of “sustainable” materials, adaptively reused and with newer technologies that minimize energy consumption.

“Razing historic buildings results in a triple hit on scarce resources. First, we are throwing away thousands of dollars of embodied energy. Second, we are replacing it with materials vastly more consumptive of energy. What are most historic houses built from? Brick, plaster, concrete, and timber are among the least energy consumptive of materials. What are major components of new buildings? Plastic, steel, vinyl, and aluminum—among the most energy consumptive of materials. Third, recurring embodied energy savings increase dramatically as a building life stretches over fifty years. You’re a fool or a fraud if you claim to be an environmentalist and yet you throw away historic buildings, and their components.”

—Donavan Rypkema 2006, Bridging Boundaries – Building Great Communities, Regional Smart Growth Conference/h3>No Delta in Historic Building Operational Performance

Data from the U.S. Energy Information Agency suggests that buildings constructed before 1920 are actually more energy efficient than buildings built at any time up until 2000, when new technologies and materials allowed for greater energy efficiency. In fact, in 1999, the General Services Administration (GSA) examined its building inventory and found that utility costs for historic building were 27 percent less than for more modern buildings.

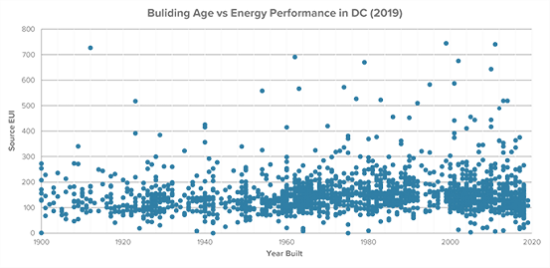

Additionally, the District Department of Energy & Environment conducted a study, analyzing the energy performance data provided through its benchmarking regulations, and determined that there is no correlation between building age and performance.

There are a variety of retrofitting techniques which can be employed in historic structures to ensure reduced energy consumption, many of which are based on interior work not usually subject to oversight or review by jurisdictional commissions. The most common and effective include:

- • insulation to floors, walls, roof, attic, weather stripping

- • ensure historic structures “breathe” through eaves and other common openings

- • install ground-source heat pumps

- • utilize internal fans, porch fans, more efficient lighting such as LED

- • install skylights on less significant surfaces to promote natural light and heat as well as drapery, blinds and awnings

- • “swamp coolers” – natural (evaporative) cooling systems

The most important energy drain, and the issue that consistently provides the most controversy across jurisdictions are windows. Many property owners are content to replace old-growth wood frame and original glazing with vinyl replacements that in most cases, materially impact the historicity of a structure, are not repairable, and have a shorter lifespan than traditional materials. While manufacturers claim that newer window solutions are more efficient, there are a number of steps a property owner can take to improve window efficiency. For example:

- • Heat loss through framing (not glass) can be addressed with sealants, weatherstripping, and brick mould.

- • Storm windows are usually more efficient than newer double/triple paned windows. They are also repairable and replaceable with a smaller carbon footprint than a window unit.

- • Early wood frames are more durable than synthetic frames and are non-toxic.

- • It is generally less costly to repair and enhance windows than replace them.

The calculation of replacement excludes the environmental costs of items in the landfill and carbon used to produce the replacements.

Conclusion

Historic preservation is essential to the achievement of sustainability goals. Through adaptation, reuse, and efficiency improvements, it is possible to retain the cultural legacy of existing buildings while making carbon reductions. In fact, it is impossible to meet sustainability goals without including existing buildings, so it is imperative that local governments and the real estate community examine how to rethink the approach to the current built environment. DC’s Sustainability Guide for Older and Historic Buildings provides some key steps. More case studies and greater industry awareness and advocacy will further advance this effort. The DC Preservation League recently completed a three-part series, “Stewardship for Climate Action,” which sheds further light on next steps.

Read the article as originally published on Building Innovation Hub.