Following Function

The Following Function series explores projects in Europe and the US that pioneer the creative reuse of redundant industrial sites, and considers the implications for heritage conservation and post-industrial communities.

During the summer of 2013, I undertook a travelling fellowship to the rust belts of Germany and the northeastern United States. My study was sponsored by the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust. During six weeks on the road, I visited more than 60 projects that pioneer the adaptive reuse of redundant industrial sites. Although industrial buildings may not carry the time-depth or cultural hallmarks typically associated with ‘heritage’, they contribute something important to our cultural understanding and identity. Since they are often the economic, social and physical center of communities, industrial sites that close lead to unemployment, social disaggregation and deprivation, making investment and commercial reuse problematic but all the more important. In a post-industrial age, the debate to decipher the cultural significance of our industrial heritage and its potential to help regenerate struggling communities is only just beginning.

Germany

In Germany my focus was the Ruhr Valley, a vast industrial landscape and the largest urban agglomeration in northern Europe. I visited some of the 120 projects implemented by IBA Emscher Park (1989-1999), a region-wide urban restructuring program to revitalize abandoned industrial sites and reverse the environmental damage caused by two centuries of heavy industry. Fourteen years after its completion, the regenerative impact of the IBA and its future challenges are becoming apparent.

United States

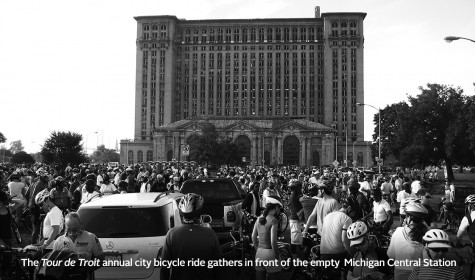

In the US, I traced the industrial network from the Brooklyn Waterfront, along the Erie Canal to Buffalo and Detroit. My itinerary was organized around the buildings depicted in early modernist manifestos by Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn and Le Corbusier, examples of the early 20th century American industrial vernacular that directly inspired the Modernist Movement. The projects demonstrate varied reuse models and different patterns of ownership, from private developers to philanthropists and government agencies. They also illustrate the commercial commodification of industrial redundancy, the role of communities in the redevelopment process and how decisions about industrial sites as ‘heritage’ are made.

SLOW BURN | Buffalo, New York

Silo City

Marine ‘A’ Grain Elevator (1925)

Buffalo, NY

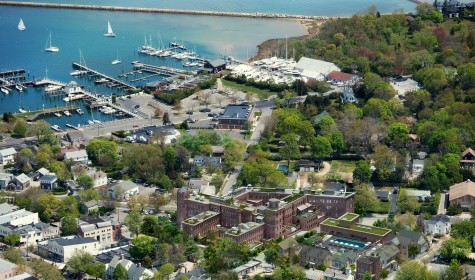

The city of Buffalo, situated at the confluence of the Great Lakes and the Erie Canal, was the focus of grain transshipment from the western prairies to the eastern seaboard for over a century. When English novelist Anthony Trollope first visited Buffalo in 1858 it was already “the great gate of Ceres” and was soon to become the world’s largest grain port.

The slow process of manual grain transfer between the ships of the lakes and smaller canal vessels was transformed in 1842 by local entrepreneur Joseph Dart. His bucket elevator system scooped grain from boats into vertical bins using a steam driven belt, giving rise to a curious new building typology–the grain elevator–made first from timber, then steel and ceramic tile, and eventually concrete. Today, Buffalo’s grain elevators comprise the most outstanding collection of extant elevators in the US and collectively represent the variety of construction materials, building forms and technological innovations that revolutionized the handling of grain across the world.

The impact of Buffalo’s silo skyline was also aesthetic. Photographs of American grain elevators were hugely influential among the European avant-garde when they were published by Walter Gropius in 1913. Europeans looked to American culture as a means of renewing and regenerating their own, celebrating the derivation of form from functional and structural inevitability as the vernacular for industrial times. Erich Mendelsohn visited Buffalo in 1924 specifically to photograph and draw the “stupendous verticals” of its “mountainous silos”. Reproducing Gropius’ photographs in Vers une Architecture, Le Corbusier heralded the grain elevators as, “the magnificent fruits of the new age”. Images of grain elevators and daylit factories became staples of modern architectural doctrine, forging the dialectical confrontation between sculptural form and gridded space—the hallmarks of the International Style.

Horizontal conveyor on the bin floor inside the American Elevator (1906), Buffalo

Grain hoppers inside Marine ‘A’ Grain Elevator (1925), Buffalo

Buffalo’s Grain Elevators Today

Today, Buffalo’s grain elevators still form an extraordinary landscape of sculptural verticality clustered along the waterfront. Although a small number of sites have been demolished, nearly twenty elevators dating from 1897 to 1954 have survived the collapse of the Great Lakes grain trade. Material evidence of a prosperous past, they are symbolic both of the city’s downturn and its hope for a vibrant, post-industrial future. In the extraordinary lexicon of the region’s world-class architectural heritage (Buffalo is home to seminal works by great American architects Henry Hobson Richardson, Frederick Law Olmsted, Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright), their significance is increasingly acknowledged. However, with only a few sites remaining in use and most abandoned, Buffalo’s grain elevators are at risk of wide-scale and imminent loss.

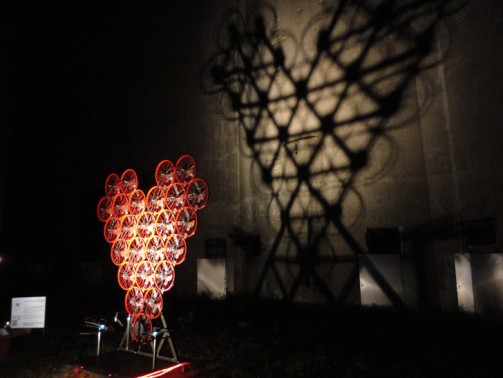

Recognizing that the Buffalo grain elevators are at risk, a local businessman bought the group of four silos at the back of his metalwork factory in 2006. Tightly arranged in the loop of the river, one has been repaired and returned to use as a commercial grain store while the other three are now part of an extraordinary experiment in slow-burn regeneration. Having prevented their demolition, substantially removed commercial pressure and spent six years clearing rubble, the initiative gives the grain elevators of ‘Silo City’ both time and public access to see if they can find their own way forward. New uses are evolving organically and intuitively through the interest of local people, underpinned by a strong sense of custodianship. University of Buffalo students are regular visitors and are encouraged to think of this architectural playground as their own. The City of Night arts festival is now in its third year and welcomed 15,000 visitors to the site over a weekend in June 2014. Silo City is already becoming a laboratory for the arts and industry, with cavernous spaces transformed through music and sculpture, urban sport, and heritage tourism. Interpretations and collaborations are emerging, because the owner is open-minded enough to welcome them. Rather than Le Corbusier’s insistence on function, Silo City’s evolving uses speak more to Aldo Rossi’s understanding of grain elevators as, “the cathedrals of our time’ and admiring them, not for just purity of volume, but for their marking ‘the passage of time, the slow evolution of collective work.”

City of Night Art Festival, 2013

Silo Art Installation, 2013

Torn Space Theatre performance inside Marine ‘A’ Grain Elevator