Openness + (in)Security

"Ultimately, the notion that an excess of security could actually make us less safe, however seemingly counterintuitive, affords us the possibility to consider how to design not just for physical security, but also for physical insecurity, by adopting an approach that is less motivated by deterrence and exclusion, and refocused on equity, diversity, and inclusion."

Jill Cavanaugh, AIA, AICP, Partner

Introduction

Openness and security are basic elements of contemporary civic architecture. While traditional security planning relies on the premise of deterrence, and therefore 'exclusion', democratic openness is inherently associated with 'inclusion'. In the wake of 9/11 and the current pandemic, architects, landscape architects, and urban designers are tasked with resolving this perceived paradox: to simultaneously welcome and deter; to bring people together but also keep them apart. However, this conflicting design objective need not be a limitation. Arguably, it may signal a new approach to physical security, one that places equal emphasis on inclusion as well as deterrence.

Architecture and design must reflect the society it serves. In the last half century, its pendulum has swung between extremes. In the late 60s, Urban Renewal policies emphasized the belief that the built environment should impose social order. This was followed in the late 70s and 80s by an individualistic and self-expressive Postmodernism. In the 90s, new social movements rooted in civic awareness such as accessibility and sustainability began to reshape policy and design. Then, in the wake of 9/11, there was a paradigm shift. Borne out of a singular, significant large-scale domestic event, rather than a continuum, the architectural response to 9/11 was not a logical extension of, or mindfully resistant to, what came before. It was nevertheless extreme. The resultant physical and operational security strategies exuded vigilance, implying social order. Yet in the intervening decades, a new zeitgeist emerged. Today, traditional social structures and their attendant power, imposition, and exclusion are being challenged. The current pandemic, compounded by the ongoing racial tension, reminds us that we are again at a moment of extremes.

So if architecture must be reflective of the society it serves, we have a responsibility to mediate exclusion and inclusion and reconcile security and openness without compromising public safety. Can security be inclusive? What will be the next act for openness and security in civic architecture to both inform and reflect the next generation?

Civic Architecture

Classical architecture is based on the principles of strength, symmetry, and proportion. For more than two centuries in the US, civic architecture has been defined by these formal characteristics, representing a sense of power commensurate with America's perceived place in the world. However, at several watershed moments in history, architects have been challenged to respond to movements or events that required building modifications to accommodate things that were unforeseen at the time of the original design, such as accessibility, sustainability, and security. In the past 50 years, a combination of legislation and sentiment has compelled us to invest in the retention of existing buildings. Yet the original design of purpose-built buildings is often at odds with contemporary society and its ethos. For example, grand monumental stairs undermine ADA compliance; closed perimeter office layouts conflict with the desire for open, daylit workspace environments; and the porosity of successful public places creates security vulnerabilities.

Interventions in existing public buildings that respond to contemporary challenges must be cognizant of the past and mindful of the future. Just as the original architects couldn't anticipate that their design innovations might become future liabilities and deficiencies, neither can we adequately or reliably anticipate tomorrow's unforeseen issues or threats.

Planning for Security versus Openness

Security planning addresses current issues and future controls to mitigate threats, reduce vulnerabilities, and create resilience to safeguard assets. Security plans are specific to individual organizations and must align with their goals and objectives. Fundamentally, security plans define specific assets, threats to those assets, and resultant methods to mitigate those threats.

In buildings, security strategies encompass physical, operational, and electronic measures. Typically, these measures work in concert to create a layered approach, comprising both visible and invisible elements, to represent an overall image of resilience. However, specific security approaches and strategies are based on specific threats to specific assets, so depending on an organization's mission, goals, and objectives, the projected image and method of representation varies. For example, in developing security plans public organizations, institutions, and agencies must balance a variety of human factors (the degree and intensity of public access), physical factors (the location, context, and setting), and operational factors (organizational assets). Security planning relies on analysis and prioritization of this combination of factors to represent a specific physical security approach.

In the aftermath of 9/11, security responses were immediate. Almost overnight, magnetometers and jersey barriers became the pervasive language of physical security. However, in the past two decades, the level of sophistication in threats, threat awareness, and threat mitigation has grown exponentially. Accordingly, our behavioral response and tolerance to physical security has also evolved. Yet the public perception of physical security in civic architecture remains an opposing struggle between openness and deterrence, a cautious and hesitant welcoming.

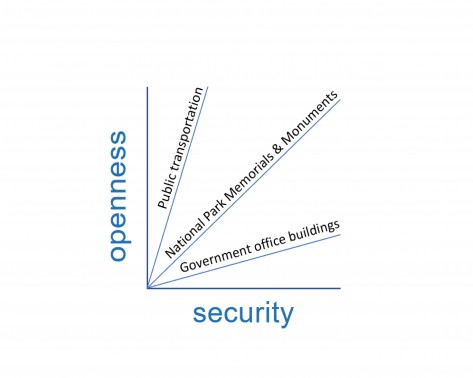

Figure 1.1: The spectrum of security and openness in public buildings

For example, consider two agencies whose primary missions are to serve the interest of the American public. The National Park Service (NPS) and the US State Department must consider the visitor experience, public perception, and symbology of their buildings, landscapes, and structures when developing plans for physical security. However, they have distinct approaches to physical security planning, applying the proportion of openness to security in different ratios because they are representing their mission in very different ways (See Figure 1.1). The NPS mission is focused on the preservation of natural and cultural resources for future generations whereas the State Department mission is driven by diplomacy and advancing the safety and economic prosperity of the American people. While both agencies provide a high degree of security for visitors, the NPS often pursues a less visible strategy, discretely incorporating security elements by embedding them into the surrounding environment. Conversely, in diplomatic buildings domestically or overseas, the State Department implements a more overtly visible physical and operational security strategy. As a result, the perception of openness remains high at National Parks but relatively low at government buildings.

Planning for Security and Insecurity

Physical security and the polemic of security and openness has taken on new relevance as the profession of architecture encounters another significant moment, one which recognizes the unbalanced demographics in the profession and the effect that a lack of multivalent points of view and collective experiences has on the built environment. This movement acknowledges that the reflection of society upheld by architects has been obscured by the historic lack of diversity, equity, and opportunity in the profession. The next generation of designers will be more diverse and will likely have directly experienced and confronted the effects of inequity and exclusion embedded in traditional power structures. As a result, the next generation may approach design solutions from a basic posture of openness and inclusion. In addition, organizations, agencies, and institutions will be comprised of a more diverse constituency and leadership that might be more willing to reflect in their missions, goals, and objectives a less traditional outlook, one not steeped in the conventional representation of strength and power.

Just as building interventions today must correct design deficiencies that were once upheld as models of then-current technology and progress, traditional security planning must move towards a new approach that does not polarize but actively mediates exclusion and inclusion, closeness and distance.

Throughout history, civilizations have relied on basic strategies like walls to keep people out. However, effective strategies are based on specific threats. Threats are dynamic and change. Consequently, static interventions lose their effectiveness. The permanence of interventions and their inherent effectiveness must be measured against the nature of the threat. Following 9/11, there was a clear concept of a specific threat. However, in the past 20 years, the concept of threat has evolved and become more multi-dimensional — politically, racially, and culturally. To compound matters, there is an emerging new public health threat, one that is invisible and requires social distancing. The pendulum continues to swing between extremes and architects, landscape architects, and urban designers must respond.

It is not responsible to posit scenarios without any physical security, and the field of biometrics is not yet capable of obviating conventional physical security measures, but the fundamental mindset towards both representation and perception must reflect the society we serve.

In 1943 in his Theory of Human Motivation, psychologist Abraham Maslow posited that safety is a basic and primitive need. His theory suggests that security, order, law, stability, and freedom from fear all need to be satisfied before individuals can attend to more complex needs, such as socialization and self-actualization. Conversely, a state of insecurity results when those needs are not met. Insecurity is underpinned by fear, shaped by our past experiences, and guided by perception and how we interpret the world around us. When individuals interpret environmental information as potentially threatening, there is an emotional response that raises our vigilance. However, social scientists suggest that as individuals become more acclimated visually to highly secure environments, their threshold for what triggers their insecurity is lowered. For example, consider the difference in reaction to a car backfiring on a suburban street versus a non-permissive environment like Afghanistan. This would suggest that highly fortified environments instigate reactive approaches to insecurity that may have unintended consequences in the basic pursuit to mitigate fear. Arguably, the proliferation of firearms, construction of border walls, and use of military force to quell civil protest is doing more harm than good.

In the current pandemic, as public spaces are overlaid with ad hoc measures to maintain distances and regulate behavior, there will inevitably be cognitive changes that affect how we inhabit space and relate to each other, recontextualizing the perceived paradox of security and openness, closeness and distance.

Ultimately, the notion that an excess of security could actually make us less safe, however seemingly counterintuitive, affords us the possibility to consider how to design not just for physical security, but also for physical insecurity, by adopting an approach that is less motivated by deterrence and exclusion, and refocused on equity, diversity, and inclusion.

As traditional power structures and the demographics that have long underpinned those structures are being challenged in an unprecedented way, the classical model of strength, beauty, and proportion must recognize a new archetype, one representing minorities, women, and people of color. In doing so, the approach to physical security should be less focused on architecture overpowering people and more intent on representing a shared experience, an architecture that once again empowers people.