Following Function

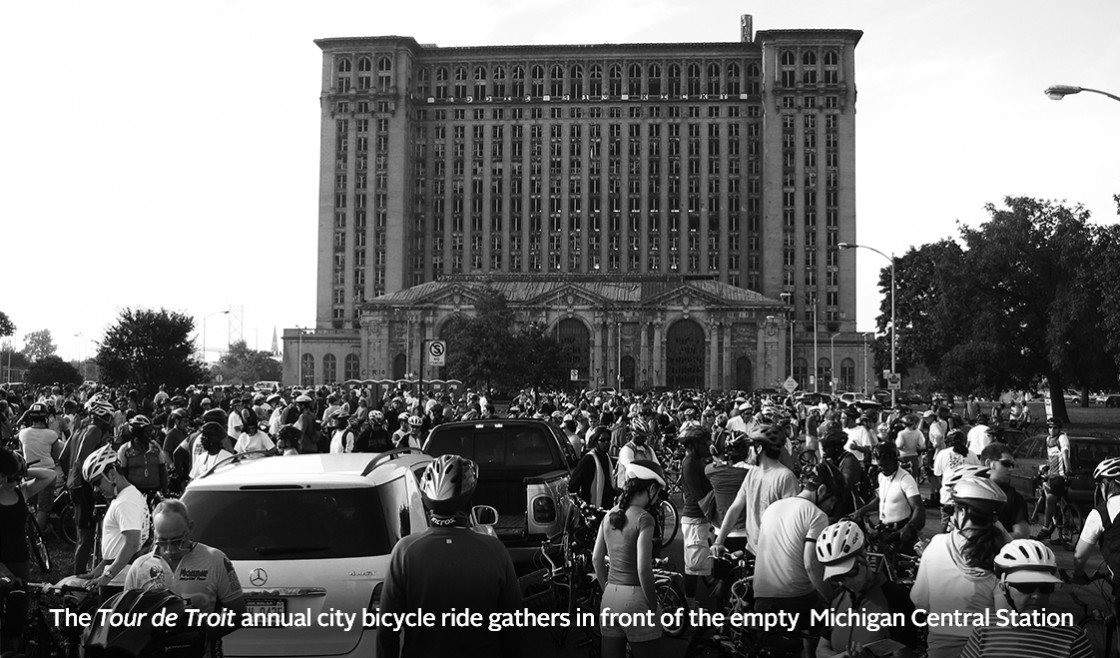

Detroit has become a symbol of post-industrial distress. Ruin voyeurs photograph scenes of overwhelming decay and the uncanny incursion of nature into spaces once dedicated to the manmade. But just as they overlook the underlying sadness of dereliction, so they ignore the vibrancy of an active city with a population working to translate loss into opportunity.

When Le Corbusier put forward utopian plans for a linear industrial city, he was inspired by Detroit. The Motor City of the 1930s functioned as an interconnected locus of production within which industrial plants, worker housing, distribution networks, commerce and civic activities were organized. The collapse of the motor industry, history of racial division, abandonment of the city’s historic core, rapid suburbanization and erosion of the tax base have burdened Detroit with a metropolitan landscape poorly adapted to the innovation it desperately needs. With some forty square miles of vacant lots and one third of buildings abandoned, space is Detroit’s greatest liability and its greatest asset. After three years of study and consultation with a broad spectrum of stakeholders, Detroit Future City published its strategic framework in January 2013. A key concept is the consolidation of Motor City’s redundant land into a “canvas of green”. The formalization of a new connective landscape is an affordable response to rationalizing the city’s infrastructure, redefining neighborhoods, remediating industrial contamination and producing food. Although very different in character to the industrial city system of the 1930’s metropolis, it could provide a new productive network for sustainable transformation.

Industrial Heritage Overlooked?

As the concept of Landscape Urbanism gains traction, the regeneration potential of the many abandoned industrial sites is only peripherally discussed. At the same time, the growing anti-blight movement supports communities in diffusing the host of social problems associated with abandoned buildings by demolishing them. Detroit’s industrial heritage is of international importance and it is hard to understand why the Motor City’s extraordinary legacy is not central to the debate about its future. As Detroit demolishes its way toward revitalization, a comprehensive assessment of its heritage assets, proper safeguarding and creative reuse models for regeneration are urgently needed.

All Eyes on the Packard Automotive Plant

In the absence of City-led initiatives, private enterprise and charitable foundations are driving change. Over the last year, Detroit has been the focus of an unlikely land rush as investors from around the world scramble to buy vacant properties in a bottomed-out market. The recent purchase in a tax foreclosure auction of the Packard Automotive Plant by a Spanish entrepreneur has caught the city’s attention. The 3.5 million SF Packard Plant (Albert Kahn, 1903) has gained notoriety as the largest abandoned industrial complex in the world. The first of the modern steel, glass and concrete factories to be built in America, the Packard Plant pioneered the use of reinforced concrete in industrial construction and is of international heritage significance. Covering a campus of 40 acres, incorporating 47 buildings and stretching for over a kilometer along Concord Street, the site has been extensively vandalized. Frequent fires and the repeated theft of metal for scrap have caused sections of the structure to collapse. Even more shocking is the distress of the community immediately adjacent. Once neat plots of workers’ houses have overgrown and merged into a meadow. The school is in ruins and roads are barely passable with pot holes and refuse. Some houses are still occupied, most are derelict and many missing altogether.

Packard Automotive Plant Interior

Imagination Station Corktown, Detroit

The Packard Automotive Plant in the 1930s

Detroit has witnessed a few miracles of redevelopment in recent years. The Westin Book Cadillac, Double Tree Fort Shelby and the Broderick Tower all found new life after decades of abandonment. However, unlike Packard, these projects are in Detroit’s busy downtown, meeting a market demand for hotel or residential. The Packard site off East Grand Boulevard near Mount Elliott remains isolated. The Detroit Future City Plan envisions that while the northern edge of the plant near highway I-94 might find new industrial use, the majority of the factory site and adjacent neighborhood would be replaced by green belt, either for farming or reforestation. This is at odds with the new owner’s aim to restore the historic plant, piece by piece, for commercial, residential, leisure and light industrial use over a 10-15 year period at an estimated cost of $350 million.

Visiting the Packard Plant, its sheer scale, extent of decay and the distress of the neighborhood make meaningful regeneration hard to imagine. Many buildings are in a critical state of disrepair, with parts of the complex unused since the 1950s. The site is choked with refuse, the ground contaminated and infrastructure crippled or obsolete. Having purchased the plant for $405,000 in December 2013, Packard’s new owner has paid off the outstanding taxes, secured the site and is undertaking a clean-up operation on a grand scale. By employing those who would otherwise continue to strip the buildings for scrap, he hopes to provide employment while protecting his property. Having converted over a hundred abandoned buildings in Spain and Peru, his regeneration model is to work through the site section by section, starting with the creation of a home and office complex for himself and his team. These are positive first steps and investors with an appetite for tackling unruly industrial behemoths are rare. In media interviews, the new owner’s emphasis is on the importance of history, the nobility of the factory and its significance to the city’s cultural identity. Parts of the building are salvageable but, if the Packard Plant is to endure, some hard decisions must be made. The site does not have statutory protection (the City of Detroit has recently pushed for demolition) and the difficult balance of heritage value and commercial pressure presumably rests with the owner. Responsible decision-making for the future of a site as significant as the Packard Automotive Plant needs to be collaborative, involving a broad spectrum of stakeholders. Establishing the condition and relative heritage significance across the complex is an essential part of the development process.

Creative Regeneration

The sale of the Packard Plant is just part of an extraordinary chapter in the phenomenon of Detroit. As attitudes shift from ruination towards regeneration, the city’s problems are so profound as to present an opportunity to envision radical change. At present, the city’s exceptional industrial heritage is not shouting loudly enough. If an apparently intractable problem like the Packard Plant can attract investment precisely because of its industrial authenticity, it may inspire creative regeneration elsewhere. Urban strategies that build on the Motor City’s rich industrial legacy should enable Detroit not just to redevelop itself, but to reimagine what a post-industrial city ought to be.

The Packard Automotive Plant today